Science dissemination

Sharing your research with the rest of the world can be very challenging. Sometimes you may need to target a broader audience than simply the colleagues in your particular research field. Colleagues in other communities or disciplines are already less likely to read about your work. When it comes to sharing your research with the general public, things become even more difficult.

There are several reasons why we all should aim to disseminate our research beyond our universities and scientific communities. For instance, it might be essential to explain your research to a general audience because you are doing it thanks to some public funding. In such a case, it is a social duty to inform the citizens about your findings and make your research comprehensible. It’s a virtuous circle that produces culture and participation, and in return, can pay for new investments in research.

Another reason is to attract the next generation towards science and your specific research field. This is an aspect that is often underrated because it hasn’t an immediate economic and/or social recognition return, but that is critical in the long term. Undergraduate students can orient their education choices and be our future colleagues and enlarge our research community. It’s vital then to let them know that your research exists and might be interesting for them. This would also benefit and increase diversity in the community and reach all those students for whom computer science is not among the options because of societal, demographic, or socioeconomic factors.

In this context, it is still tough for scientists to involve the uninitiated on very specific topics that seem to have almost no connection with their everyday lives. However, many different techniques, tools, and languages have been studied and gradually refined over time. With the increasing amount of information available online, it is becoming more and more important to be concise and attract the audience’s attention from the very beginning. Video might be one of the ways to go.

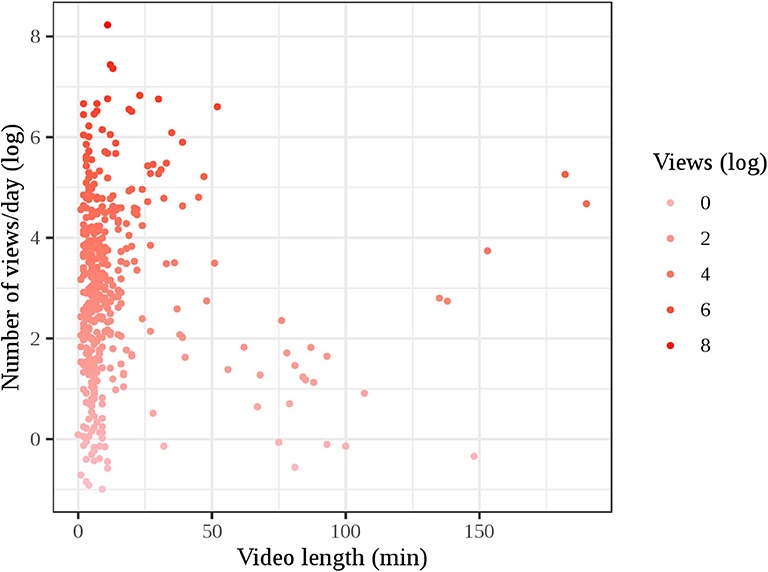

Number of views per day (log) x video length (min). Plot courtesy of “Communicating Science With YouTube Videos: How Nine Factors Relate to and Affect Video Views” by Velho et al.

Videos about science

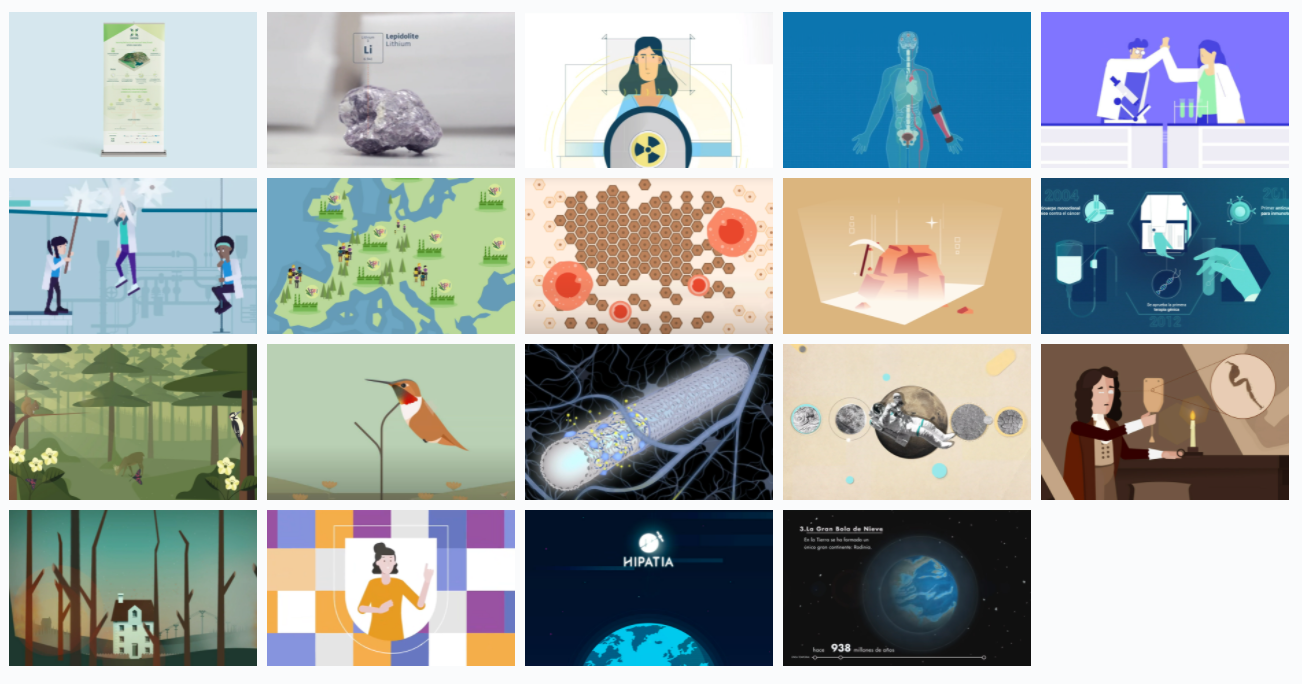

Videos about science have become more and more popular over the last decade as they are a low-barrier medium to communicate ideas efficiently and effectively. Short videos from 3 to 5 minutes are ideal because they are long enough to explain a concept and sufficiently short for viewers to decide if they are interested. We all have learned about the advantages and disadvantages of this medium during the last year of the pandemic. The format of the conferences has changed, and video abstracts are now a standard. However, video abstracts are intended for peers and not for a broader audience. When disseminating science, complex concepts should be made accessible for the largest audience possible. In such a case, motion graphics and animated storytelling can be a possible solution. Through the process of abstraction in an animated representation, we can effectively simplify the concept we want to transmit. The style, colour palette, transitions, aesthetic and functional choices can all concur to convey the main message.

Examples of scientific dissemination projects. Image courtesy of Scienseed.

Now, I can’t say this process of abstraction is easy. It takes time, many iterations over the script and many drafts before coming up with something good. You have to learn to work with visual designers who do not know anything about your research. We experienced this when working on the MIP-frontiers video communication project, meant to attract young researchers in our research field. It’s very hard to simplify and abstract things you work on every day. It feels like sacrificing many details which are essential to you for the sake of simplicity. Because of that, you have to always keep in mind who’s your target audience. In the specific case of this video, there was an additional problem: we needed to cover the most possible areas in music information processing (MIP), which was quite hard. The trick we found was to trace back the history of a song that an imaginary inhabitant of the future is listening to. We managed to derive a circular story following the song from composition to recording and from distribution to the user experience. Therefore, the music is the backbone of the video, and its choice was crucial.

Making-of

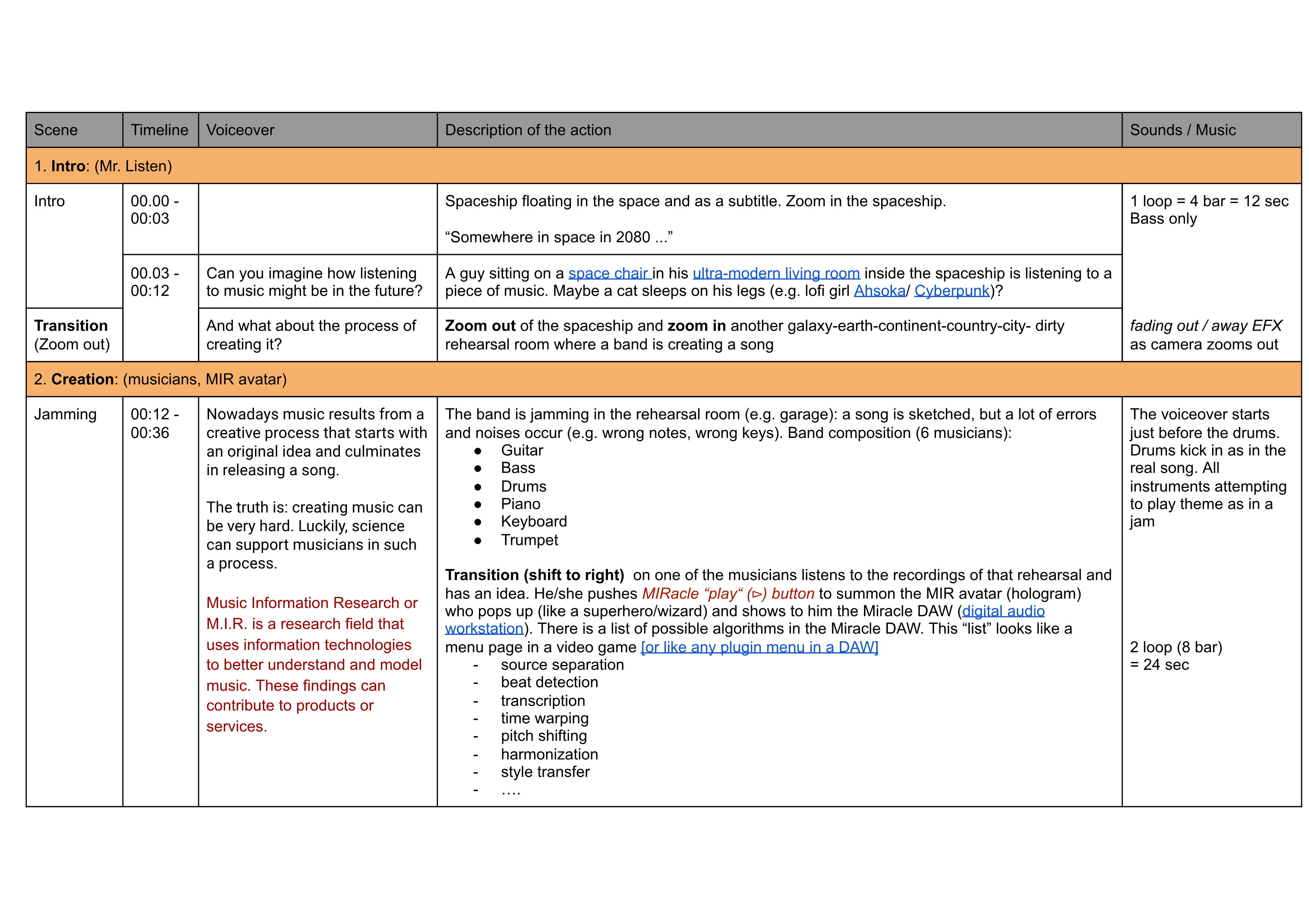

When preparing a motion graphic, you need to provide to the visual designers a script (description of the scenes), the voiceover (text that an actor needs to read and which describes the scene), and the background music. With those three elements, the visual designers built an animation on which you can then give feedback and adapt the voiceover and the music again. This process is reiterated repeatedly until convergence, when everyone is happy with the result.

Draft of the initial script of the MIP-frontiers animation

In our case, an additional difficulty was that the music wasn’t just some “background” music. It was, on the contrary, the absolute protagonist that mainly contributes to conveying the main message. The music evolves throughout the video and changes according to the MIR application we wanted to illustrate. All of this needs a not negligible effort of synchronization and composition.

Regarding the voiceover, we quickly realized how few words can fit a 3-minutes-long video. More importantly, we learned how hard it can be to summarize the vast diversity of research in our community. Moreover, there are synchronization constraints that impose a fixed number of words to express complex concepts. In the end, we reached a compromise trying to represent as extensively as possible some MIP applications.

Once the voiceover, the animation and the music are done, it is not trivial to create the final video anyway. In fact, in addition to a temporal synchronization of events, automation on the volume of the various instruments and the voice are necessary. This operation is always necessary for video production, and the role of a sound engineer is essential for an optimal result. Especially in this work, where music and its evolving parts are the protagonists, this professional figure had a particularly central role in glueing all the components.

Special Thanks

In general, it was a great experience! I learned a lot, and I’ve spent some time doing something that is not strictly related to my research, but that is a fundamental part of the scientist job. We really thank Mandela (music) and Scienseed (animation) and Alberto Di Carlo (sound engineer) for their great work!

For this video, the track Simple from the album Mandela s.t. was used. The song was remixed and remastered by Alberto Di Carlo.