Why are women still so underrepresented in science? Female scientists represent only a third of researchers globally, and things are not getting better when talking about information and communication technologies, where less than a fifth of the graduates are women.

The Music Information Retrieval (MIR) community is no exception, with less than 20% female participation at ISMIR 2019, the conference of the International Society for Music Information Retrieval. Despite the efforts of organizers this year to promote diversity in the choice of the keynote and the session chairs, the gender gap is still evident when looking at the author and attendee statistics.

Presence of women at ISMIR 2019

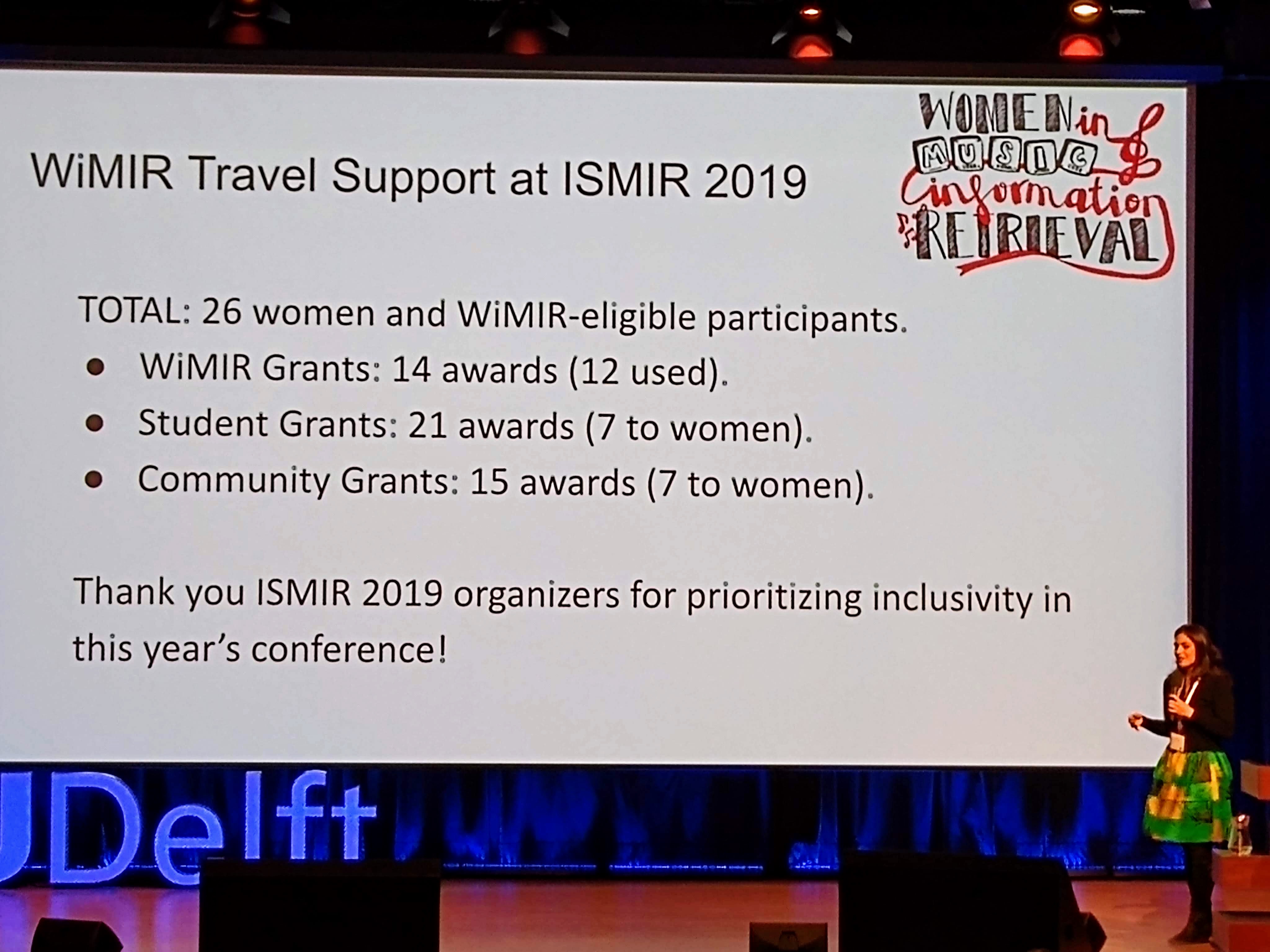

Much still needs to be done to bring women into the community and to reduce the gender gap. For this purpose, Women in Music Information Retrieval (WiMIR) – a group of people within ISMIR – has put together ideas and started many diversity and inclusion initiatives. The goal is to build a community around women in the field and create a network able to support young researchers through grants, workshops and mentoring from senior scientists. Thanks to the WiMIR grants, ISMIR 2019 female participation had a 5% increase!

WiMIR travel support at ISMIR 2019

I am starting a series of interviews with female researchers in MIR to find out more about their experiences and give an insight into young female researchers who want to start a career in MIR research. The first name on my list is Dr. Blair Kaneshiro, who is a researcher at the Center for Computer Research in Music and Acoustics (CCRMA) at Stanford University, a member of the ISMIR Board, and one of the WiMIR organizers.

Dr. Blair Kanashiro presenting the WiMIR program during the plenary session at ISMIR 2019

Whereabouts did you study?

I’m from the United States and completed all of my schooling at Stanford University. My undergraduate degree was in Music. I later returned for graduate school, completing an MA in Music, Science, and Technology; MS in Electrical Engineering; and finally a PhD in Computer-Based Music Theory and Acoustics.

When did you first know you wanted to pursue a career in science?

A career interest in science for me did not develop until graduate school. I had been working at an education company at Stanford called the Education Program for Gifted Youth (EPGY) after my undergraduate degree when Patrick Suppes – co-founder of EPGY and Emeritus Professor of Philosophy, among many other remarkable things – suggested I pursue graduate work. Dr. Suppes was actively running a neuroscience lab at that time, and offered to fund my Master’s through a research assistantship in his lab. Once there, I began to see how neuroscience and engineering could be employed to address fundamental questions about perception and music – questions I feel, three graduate degrees and over a decade later, I’ve still barely begun to answer! Sadly, Dr. Suppes passed away in 2014. I am forever grateful for his support and mentorship, and for encouraging me to pursue science in the first place. I try to pay forward what I have learned from him, as both a scientist and a mentor.

How did you first become interested in MIR?

For the first few years of my graduate study, I didn’t feel I had a “home” research community as my work was falling somewhere between perception / cognition and machine learning / brain decoding. In 2011, my classmate suggested I attend the ISMIR conference. I was immediately drawn in by the field of MIR, not only by the research topics – which to me were combining computation, perception, and application in exciting ways – but also by the community itself, which was welcoming and open to new ideas and approaches.

What are you currently working on?

These days I have two main research tracks. The first is electroencephalography (EEG) research, where I continue to use the decoding techniques I first encountered in the Suppes lab, and related approaches, to study proximity spaces of neural responses. I’m also working with analysis techniques that enable us to study neural processing of “natural” stimuli (e.g., real-world music). My second area of research focuses on how social practices around music selection and consumption are supported (or not) by present-day technologies such as streaming platforms – more in the direction of user research. In all, I really enjoy working with a variety of collaborators, study designs, data modalities, and analysis techniques to gain a better understanding of how we humans engage with music.

Are there still gender imbalances in your research environment and in the MIR community? If yes, how can we overcome that?

Yes, definitely! In fact, I was relatively unfazed by the low number of women at the first ISMIR conference I attended, if only because it was what I was used to from being in engineering classes. But there is definitely an imbalance. In terms of overcoming this challenge, the MIR community stands out in its willingness to take action. Community members (women and men) have signed on to mentor women, organize initiatives, lead Workshop groups, and serve on conference committees; and sponsors contribute extra travel funds specifically for women to attend the ISMIR conference. While there is still a lot of progress to be made, the fact that the community as a whole is already on board makes a huge difference in moving forward.

Which changes, if any, are needed in the MIR community to be more attractive to women?

Building a more diverse research community will take time. It also requires support at multiple career stages, from recruiting women into the field to retaining those who are here. We are already starting to see positive outcomes from community initiatives. For instance, the WiMIR Mentoring Program, WiMIR Workshop, and WiMIR Travel Awards can serve as entry points for newcomers to the field, and we have seen cases of WiMIR Mentoring participants pivoting into MIR-related jobs or graduate programs, and of newcomers attending ISMIR for the first time through WiMIR Travel Awards and returning in future years as full-paper authors. But how exactly does one progress from attendee to author? And how do we keep women in the field for the long term – what are the challenges there? Will our progress in recent years translate to long-term change? I hope we can all continue to examine these challenges, understand underlying factors and biases, and take steps – on a community level and in our immediate working environments – to recruit and retain more women in MIR.

What advice would you give to young girls who are considering a career in science?

I recommend taking a broad look at what types of scientific fields are out there. Maybe you have a picture in your mind of what it looks like to “do science”. In fact, science spans a vast array of disciplines – even music! Also, it’s important to recognize that there is no one way to be a scientist, and no one way to look or act as a scientist. I highly recommend browsing the profiles at #UniqueScientists to see just how diverse the people, topics, and career paths in science are today.