Few weeks ago, I attended the 16th Sound and Music Computing (SMC) Conference, which was hosted by the University of Malaga. While the theme of this year’s conference was ‘Music and Interaction’, the content of the scientific program included a wide range of topics in Sound and Music Technology. Out of 97 paper submissions, 33 of them were accepted as poster presentations, and 41 of them were presented orally in 15 minute slots. For each day, the scientific program included 3 oral sessions (6 presentations on average per session), 2 poster sessions and a keynote talk.

Keynote Talks

The three keynote speakers at this year’s conference were Elvira Brattico, Anja Volk and Mark Sandler. Each talk lasted around an hour, and each speaker presented an overview of their focus of research through recent projects they have been involved.

The first talk by Elvira Brattico had an emphasis on music perception studies that involve human participants. She stated in her talk that “From a neuroscience perspective, listening to repeated sounds, as in many music perception studies, is the opposite of listening to the ‘real’ music, phenomenologically.” Moreover, her years in neuroscientific research validated that musicians have higher brain connectivity compared to non-musicians. Anja Volk, the second keynote speaker of this year’s SMC conference, underpinned the importance of explicit computational modelling of musical concepts through analysing melodic patterns in folk music in her talk.

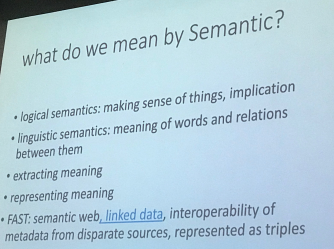

… on semantics (from Sandler’s presentation)

On the last day of the conference, Mark Sandler, head of Centre for Digital Music (C4DM), gave his keynote talk where he highlighted the outcomes of the FAST project. The FAST project, also one of the main sponsors of the conference, aims to encapsulate well-structured musical metadata in the form of Digital Music Objects (DMO). In essence, the main goal of the project is to empower people in the music production/consumption value chain via these DMOs.

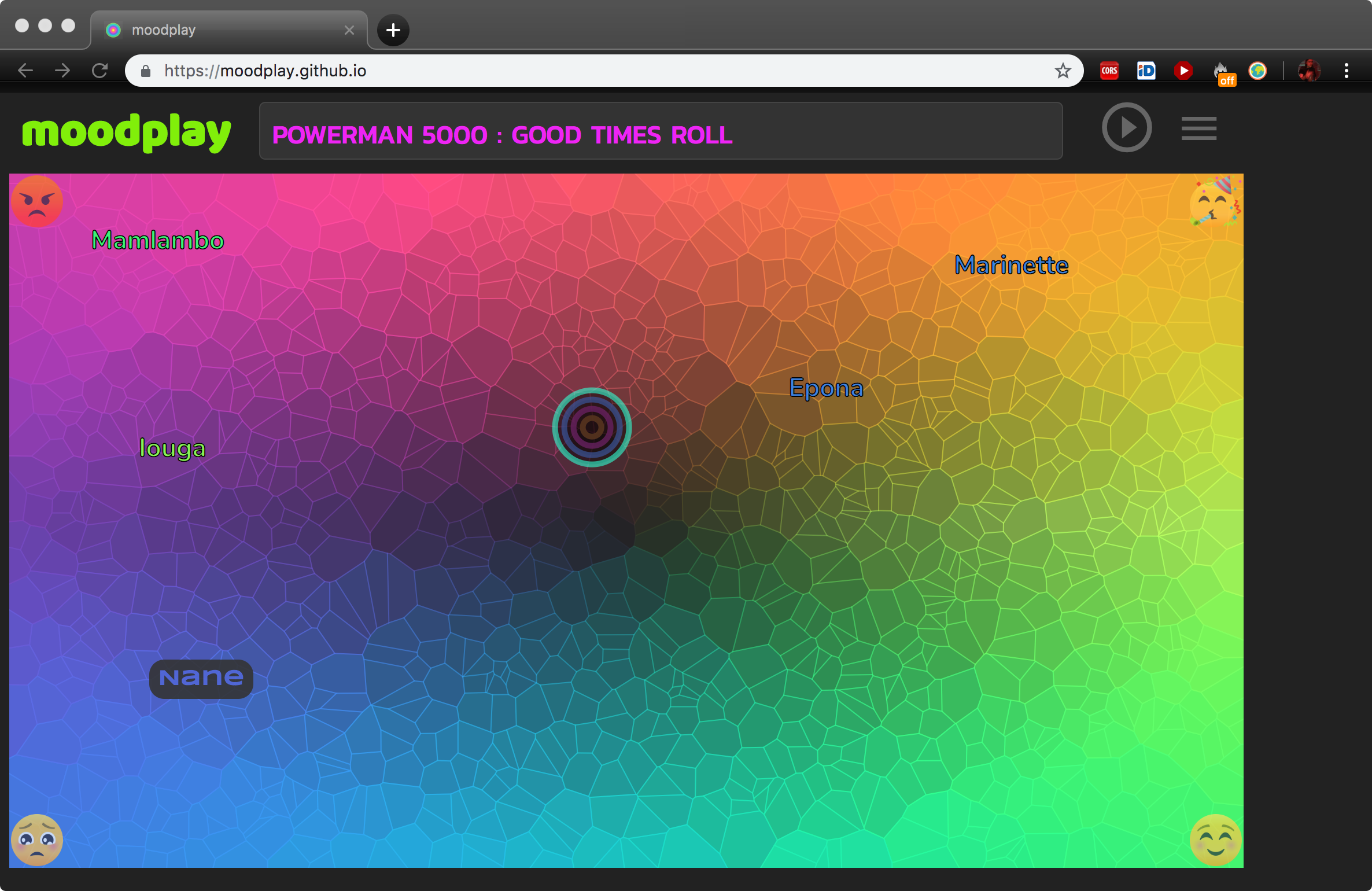

Alo Allik, a colleague from C4DM, has demonstrated one of the outcomes of the FAST project, MoodPlay. It is an online music player that allows users to collaboratively choose music by mood in the hope of enhancing social interactions in music streaming. The interface (figure below) represents tracks in a 2-dimensional mood space, where selection ranges between negative to positive on one axis, and calm to excited on the other. The users can explore the mood space and vote what kind of music they want to listen to while also being shown the preferences of other participants. The music is automatically mixed by an auto-DJ module that models various DJ-ing styles using content-based audio features that represent musical parameters such as tempo, beats, bars, keys, instrumentation and amplitude.

Scientific Program

Sonic Interaction

As the theme of the conference implies, papers focused on human-computer interaction in a musical context were highly represented at the conference. Several works in first sessions [1] had a focus on hardware solutions to the current problems in digital music instrument or interface design, such as latency [3] or digital manufacturing [2]. Some researchers conducted perceptual studies with users by measuring their reactions to everyday digital and acoustic sounds [4]. Further, the authors of [5] evaluate synthesized game effects on music perception by comparing them with actual recorded sounds.

There were a few studies related to Virtual Reality (VR) applications. In [6], the author gives a perspective on how diegetic (originated from the VR system) and non-diegetic (sourced from the external environment) sounds affect the decision-making process of VR users. In [7], the authors presented an application of ‘stringless’ guitar playing in a VR scenario.

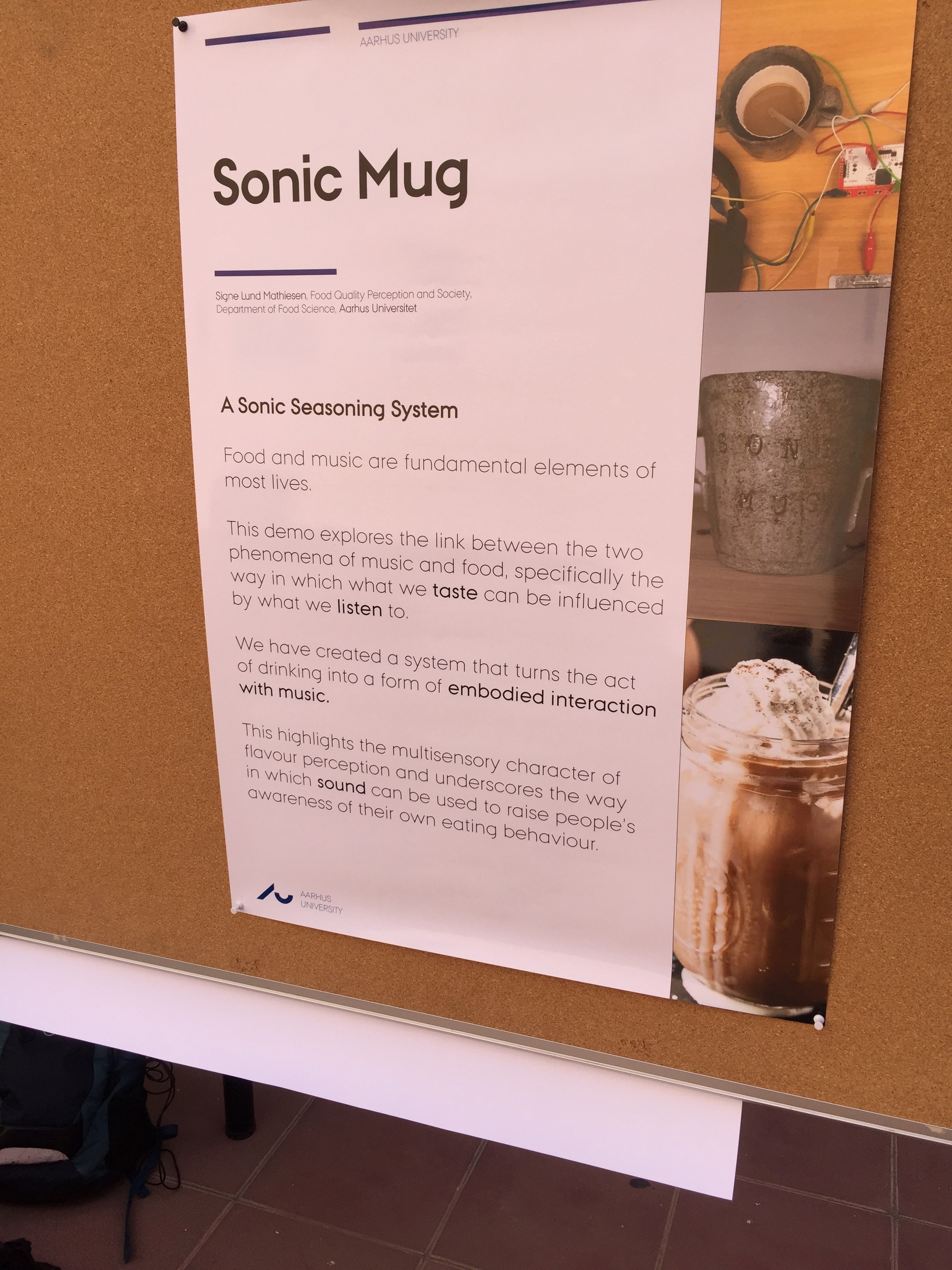

Physical modelling of human - computer interaction in the context of sonic interaction was another popular research focus in the conference. For instance, the framework seen in the picture above aims to highlight the common behavioural aspects of eating and listening via the sensors in their physical model [9]. The authors of [10] propose methods for ‘media transformations’ in the context of audio-visual performances. They demonstrated their work using an interactive glove the team designed for this study.

Arguably one of the most interesting physical modelling studies at the conference was the mechanical automatic piano tuner [11]. Even though the system is a work-in-progress, it already shows promising preliminary results.

Sound Synthesis

The study in [12] showed the significance of visual modelling for synthesizer parameter mappings in sound design. Another work [13] on the sound design / synthesis interfaces suggests that users tend to use existing presets and programs regardless of their musical background.

In [14], the authors used a variant of the WaveNet architecture for modelling circuits of different audio distortion devices. Interestingly, the authors state that 3 minutes of training data was sufficient to achieve good results. In fact, the reconstructed sounds that they played during the presentation were quite convincing.

Hsu [15] presented an application of loopback frequency modulation (FM) in sound synthesis to achieve a parametric percussion synthesizer that captures the sonic characteristics of non-linear percussive sounds.

SMC Tools

New software libraries and toolkits designed for Sound and Music Computing studies are usually interesting and have the potential to make researchers’ life a bit easier. Here, I list some of the toolkits that were introduced at the conference:

OM-AI [16] : A library written in OpenMusic language for computer-assisted music composition. This package contains implementations of popular machine learning based data classification & generation techniques.

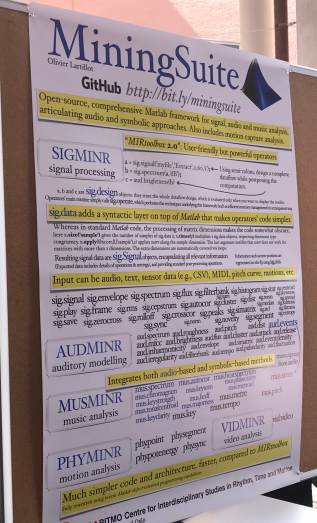

MiningSuite [17] : A MATLAB framework for signal processing and analysis for music applications, which is an extension of the famous MIR Toolbox.

OCR-XR[8] : A toolkit written in Unity, which is designed for rapid development of musical environments in extended reality (XR) applications.

MI–GEN [18]: A sound synthesis toolkit based on MAX/MSP.

MIR

Although Deep Learning was not the main focus neither the trend at this conference, there were a few interesting studies that focus on how Neural Networks operate on different music related classification tasks.Hendrick’s work [24] proposes that using directional filters in CNN architectures can be effective in tempo and key estimation tasks, even with shallow networks. The work showed the benefit of using directional filters in classifying temporal information. BachProp [25] was introduced as a sequence-based automatic music generation system using a deep GRU network. The authors have made the code available through here.

There were quite a few work on automatic chord recognition/estimation presented at the conference. [19] applies RNN-LSTM based chord estimation on a corpus of Beethoven’s string quartets. [20] demonstrated a state-of-the-art automatic chord recognition algorithm implementation in music education context. In my opinion, the system they showed in the demo session was quite robust. [21] proposes a ‘belief propagation algorithm’ for chord recognition, which is a sequential graph modelling method used in digital communication information retrieval. [22] presented a CNN-based architecture for the chord recognition task on an extended chord vocabulary that covers seventh chords along with the major/minor triads. The authors report a promising f-score of 0.97 on isolated chords on their own dataset. Last, but not least, Pauwels et. al. [23] presented a web-based framework aimed at music students in the context of chord playing.

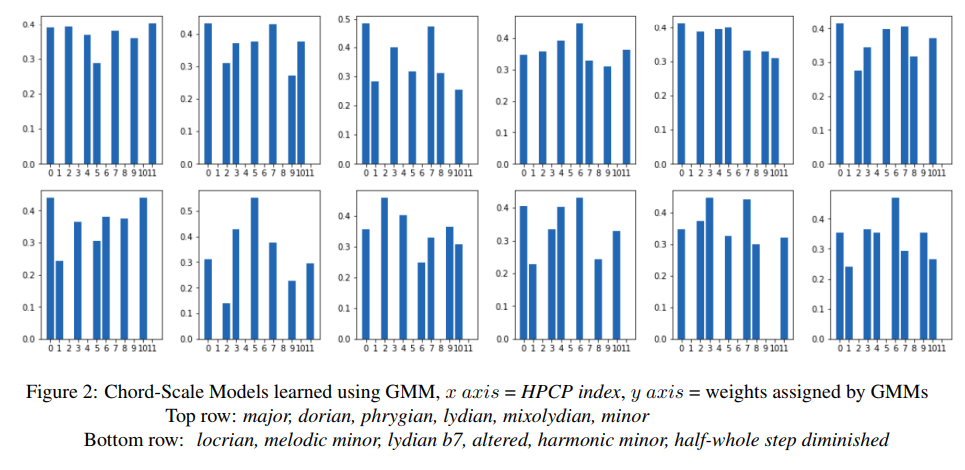

I presented my paper in this session, which was on building GMM-based scale models in the context of jazz improvisation [26]. The figure below shows the GMM-based scale models constructed on the Harmonic Pitch Class Profile (HPCP) distributions of the improvised Jazz solos. Yet, I was able to have a quick glance on other posters. There was another work on the computational analysis of improvisation where the author highlights some musical interaction based ideas for segmenting unstructured, freely-improvised performance [27].

Multi-cultural Analysis

While most computational music analyses were based on pop, electronic or Western classical music, there were some work on music from varying cultures. [28] used RNNs for generating Swedish folk music using the architectures that were previously used for Irish folk music (A demo at www.folkrnn.org). The authors of [29] investigated the link between dancers’ and musicians’ interactions through Swedish Folk Music. My colleague, Changhong Wang, presented her work detecting Glissandi in Chinese Bamboo flute recordings using HMMs [30]. [31] presented his work on vocal ornamentations in Persian classical tradition. The authors suggest that PYIN algorithm is robust enough to capture the pitch variations in the vocal ornamentations in this tradition. Last but not least, another colleague, Helena Cuesta from UPF presented their work on multiple fundamental frequency (multi-f0) modelling of choir performances in Soprano, Alto, Tenor and Bass (SATB) setting [32]. Even though there weren’t many papers regarding singing voice, this paper seemed really interesting due to highlighting the problems in multi-f0 tracking for choir singing and using the DeepSalience time-frequency representation of the sung performances.

Awards

1st best paper award:

2nd best paper award:

Best paper presentation award: