In the beginning of November, I attended the 20th edition of the International Society for Music Information Retrieval Conference (ISMIR), which took place this year in Delf, the Netherlands, and was hosted by TU Delft. Apart from keynotes, tutorials, and interactive sessions, the core attraction was the scientific programme, consisting of 114 accepted papers, whose authors had the opportunity to expose their work in both oral/poster sessions.

A number of these works proposed solutions for tasks involving two or more representations of music, being this type of problems conventionally categorised as a cross-modality music information retrieval task. Such representations include audio recordings, MIDI, sheet music images, video clips, and so on.

In this blog post, I write about two ISMIR papers which explore either a cross-modal scenario and/or analysis of music score images. The main motivation for this choice is that in my doctorate studies I attempt to solve cross-linking of audio recordings and sheet music scans in large collections. The first paper gives an important step towards retrieving a passage of music given a cell phone picture of sheet music. After that, I write about a work that proposes a solution for cross-document alignment of music scores.

MIDI Passage Retrieval using Cell Phone Pictures of Sheet Music

Imagine the situation as follows. You are on holiday in Vienna and, inspired by the classical music scene of the city, decide to visit a music-themed museum, let’s say the Haus der Musik. There you are, surrounded by music score examples, and since you might not have a music background, the images you see don’t make much sense to you. However you are quite curious about how those weird symbols are connected to the notes you hear. What if you could just pull you cell phone out of your pocket, take a picture of some bars of sheet music, and listen to this specific passage directly from your device? Such a system is what researchers from Harvey Mudd College (Claremont, CA USA) present in their recent work1.

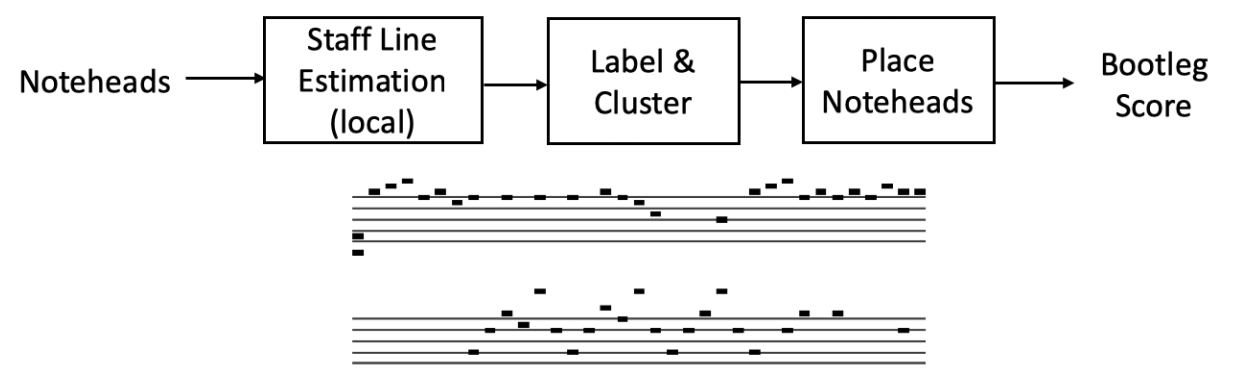

They investigate whether the aforementioned system is feasible by introducing a mid-level representation, referred to as bootleg score, that is a low-dimensional representation of music which can be interpreted as a hybrid between music score and MIDI. This feature can be understood as a coarse version of sheet music, which shows only the location of the noteheads on the staff lines. An example of a bootleg score is depicted in the bottom plot of Figure 1.

Figure 1: Proposed pipeline for bootleg projection (top), followed by an example of bootleg score (bottom)1.

Assuming that the piece of music is known by the user, the proposed system takes as inputs two modalities: a picture of a page of a music score and the MIDI file of the respective piece. Then both inputs are converted into a bootleg score and aligned and matched, so the output can be the playable MIDI passage corresponding to what is in the picture. The bootleg feature computation is briefly described as follows. On the MIDI side, this process is straightforward since, by its symbolic nature, the musical notes can be directly read from the file. The note onsets are obtained and projected into the bootleg feature space. As for the cell phone images, the authors propose the following pipeline, which is illustrated in Figure 1. First the image is enhanced, followed by filled notehead detection. Then staff and bar lines are detected, and the detected notes are clustered and projected into the new representation. Lastly, the two bootleg scores are aligned via subsequent dynamic time warping (DTW)2 and the segment in the MIDI file that best corresponds to the sheet music picture is estimated.

In addition to its novelty, good performance is achieved when compared to baseline systems. One interesting aspect is that this approach does not require any trainable parameter, only hyperparameter tuning for the image processing steps. I believe this could be the first step towards an application for cell phone or tablet devices that can be useful for either musicians or music fans. To conclude, I support the idea that the authors could have included concrete future plans to improve the system, such as how to extend the notehead detection to non-filled noted (half and whole notes), or maybe removing the assumption that the query piece is known and search it in a larger database, without informing the name of the piece to the system.

Identification and Cross-Document Alignment of Measures in Music Score Images

In musicology, different versions of scores from the same music piece are frequently compared. The reason behind this is the complex musicological process of musical edition from the composer’s manuscript to the final printed version. As a result, it is convenient for musicologists to have an efficient cross-navigation tool for identifying changes between multiple editions of a musical work. In my research, I attempt to solve the problem of linking excerpts of audio recordings to sheet music snippets, at the moment using artificial data but moving gradually to real performances. Researchers from HfM Detmold, Germany, and TU Wien, Austria, were more ambitious and proposed a system3 which automatically detects and links measures across different documents, including handwritten scores.

They formulate this task as a three-step problem. First, measures are detected and extracted from the scores. Then, a convolutional neural network (CNN) is trained to learn correspondences between similar measures. Lastly the measures are aligned in order to get a meaningful representation which compares two entries.

The data used in this work were created by the authors, in collaboration with musicologists and musicians. The dataset comprises sheet music scans from facsimilia, from the IMSLP library and also from the MUSCIMA++ dataset4. The ground truth consists of bounding box annotations of measures and mapping thereof between corresponding ones from different versions, and were created manually by musicologists and via the Android app Vertaktoid. In total, the collection comprises over 8,000 pages with over 80,000 annotated measures.

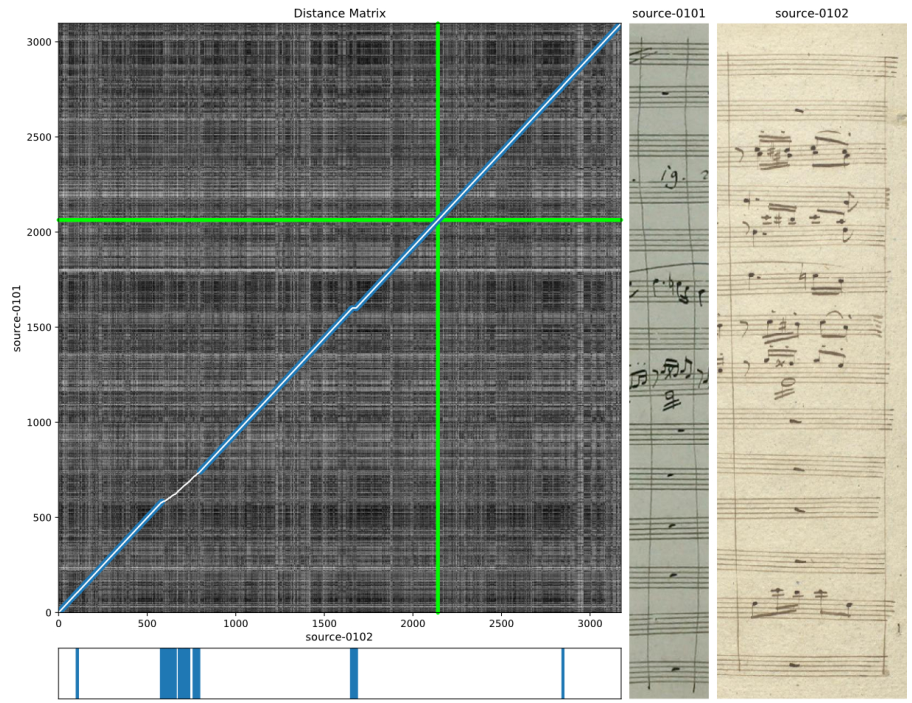

To detect bounding boxes around the measures, a framework consisting of a convolutional neural network followed by a Faster R-CNN detector5 is presented. An example of measure detection is shown in Figure 2. The detected measures are then resized to 512 x 512 pixels and sorted according to their location in the page. Then the correspondences between then are obtained via embedding space learning, a popular framework for cross-item retrieval. A CNN is trained to learn a latent representation by minimising the cosine distance between similar items and maximising this metric for dissimilar ones.

Figure 2: Green bounding boxes detected around measures in sheet music scans3

Finally, after the training is done, it is possible to compare two documents. After the measures are detected and projected onto the embedding space, a distance matrix is obtained by computing the distances between measures from one document to another. Then DTW2 is applied to the matrix in order to obtain an alignment curve which represents the measure relationships, also known as concordances.

In addition to the good results reported in the paper, the authors also propose a useful interface where the user can manually adjust the alignment curve in order to correct eventual mistakes from the system. This practical aspect showed that the authors made efforts to make their system suitable for real-life cases. To conclude, since deep learning is strongly data-driven, I would include more details about which kind of data was used. Music scores are rich in terms of instrumentation, and measures contain from one to several staves, sometimes fitting the whole vertical dimension of the page. It is reported that a large share of the dataset is represented by orchestral scores from operas (diverse instrumentation), so it would be interesting to report on the evaluation of different test splits, e.g. only orchestral or piano scores. I also was wondering how this framework could be extended to a cross-modality scenario, and when talking to the authors personally at ISMIR, they have confirmed that future plans include to perform audio-to-sheet music analysis.

References

-

Daniel Yang, Thitaree Tanprasert, Teerapat Jenrungrot, Mengyi Shan, and Timothy Tsai. MIDI Passage Retrieval Using Cell Phone Pictures of Sheet Music. In Proceedings of the International Society for Music Information Retrieval Conference (ISMIR), Delft, The Netherlands, 2019. ↩ ↩2

-

Meinard Müller. Fundamentals of Music Processing: Audio, Analysis, Algorithms, Applications. Springer, 2015. ↩ ↩2

-

Simon Waloschek, Aristotelis Hadjakos, and Alexander Pacha. Identification and Cross-Document Alignment of Measures in Music Score Images. In Proceedings of the International Society for Music Information Retrieval Conference (ISMIR), Delft, The Netherlands, 2019. ↩ ↩2

-

Jan Hajic jr. and Pavel Pecina. The MUSCIMA++ dataset for handwritten optical music recognition. In 14th International Conference on Document Analysis and Recognition, pages 39–46, Kyoto, Japan, 2017. ↩

-

Shaoqing Ren, Kaiming He, Ross Girshick, and Jian Sun. Faster R-CNN: Towards real-time object detection with region proposal networks. In Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 28, pages 91–99. 2015. ↩